Moon and Space

Moon and Space

1969

Galerie Beyeler Basel

73pp.

design by Victor Vasarely(?)

printed in Switzerland

How often do you think of a book as “inviting”? What does that word even mean in the context of printed matter? To me, it is one of the most fundamental characteristics of the medium. How might a book ask you to explore it; to navigate its text, imagery, materiality, and overall visual strategy? It’s a fallacy to believe a designer’s role is to make a book which simply looks good. That often results in an object that is comprised of a series of disparate pages which function more like independent posters than interrelated spreads. The alternative is a book which is so timid in its execution it is an utter banality to navigate. Instead, it is the mark of a designer’s generosity to create a text which fuses the beauty of the single page with one that is a joy to hold, to open, to manipulate, and explore. The next time you flip through a book, ask yourself if you feel punished for turning the page or rewarded.

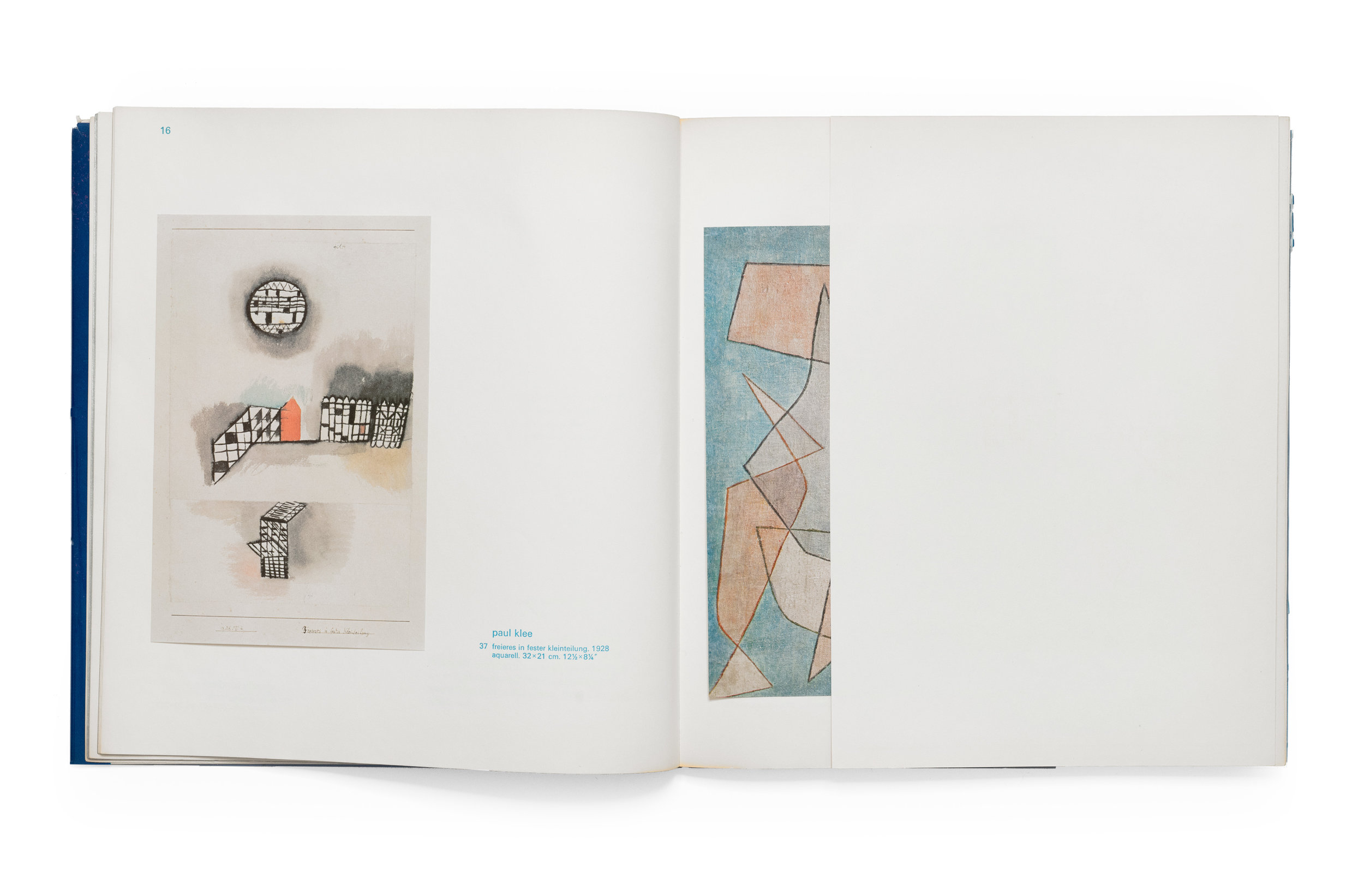

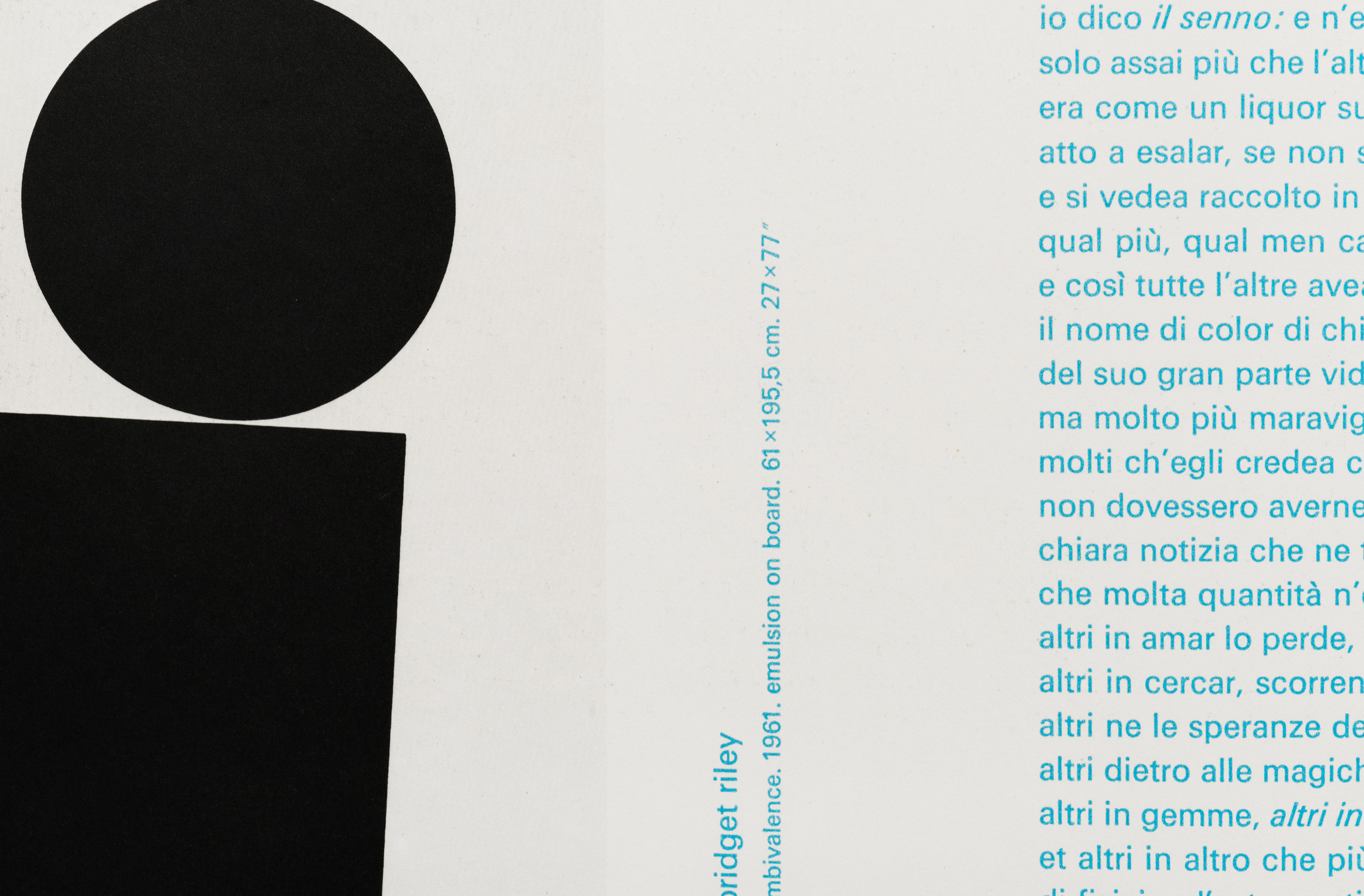

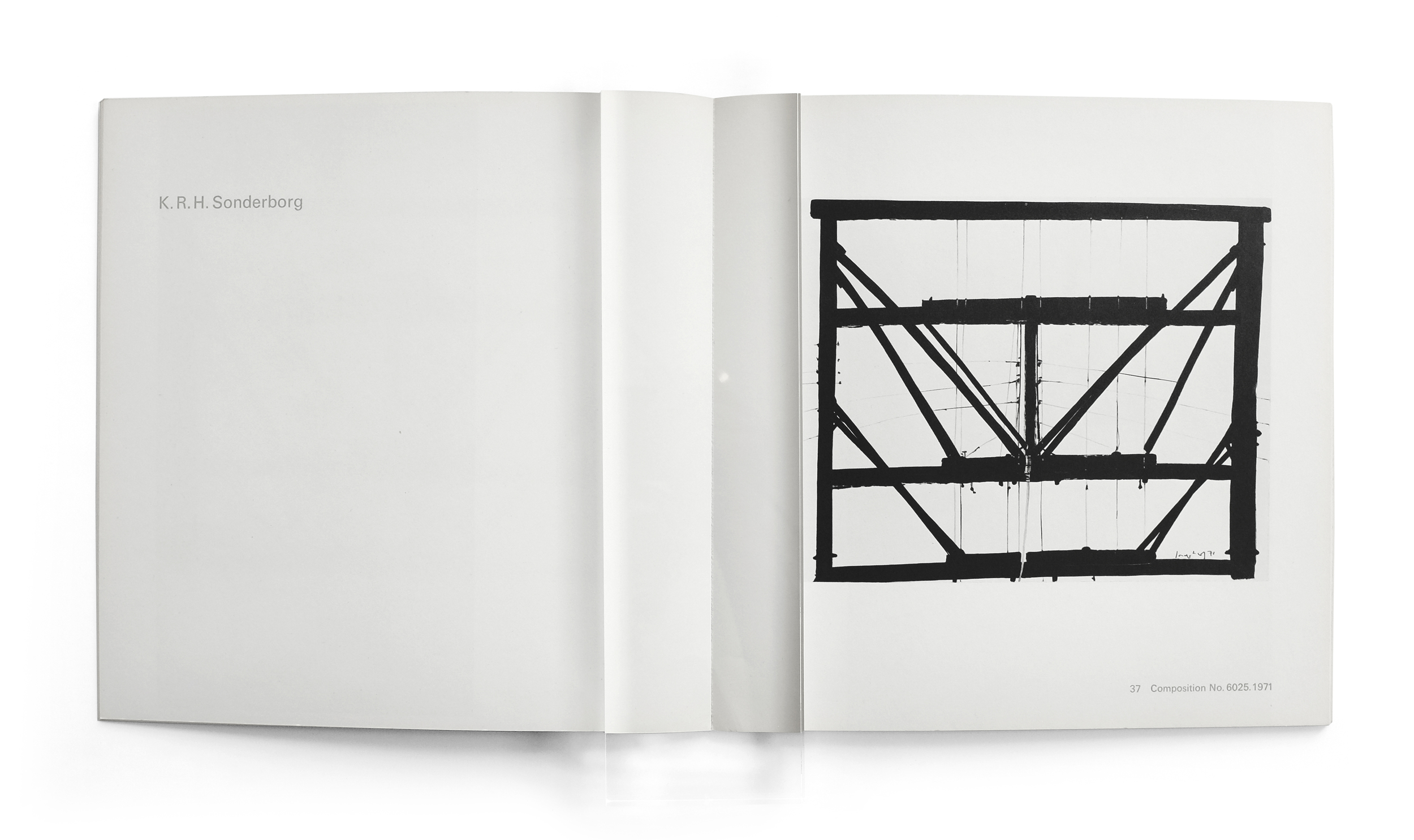

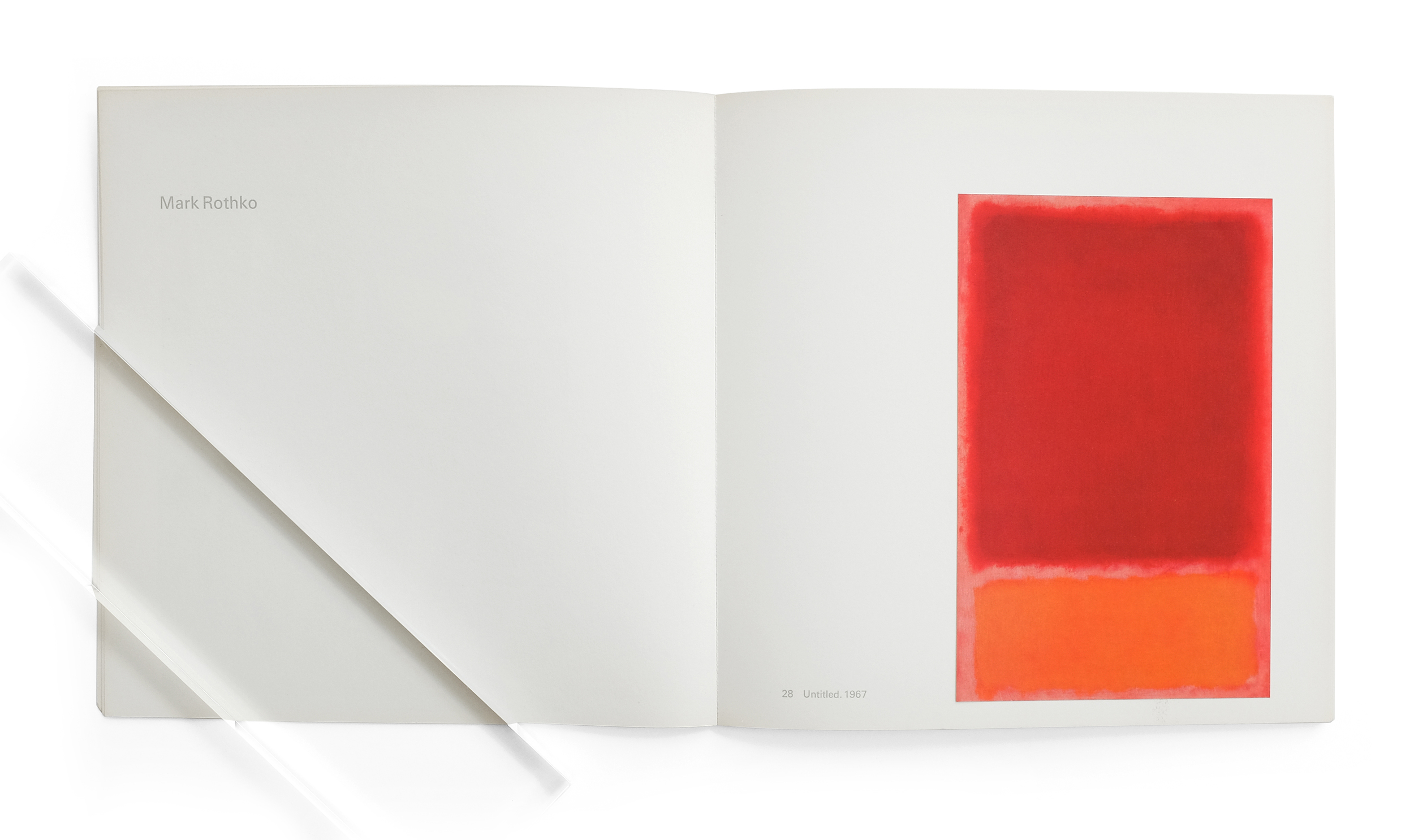

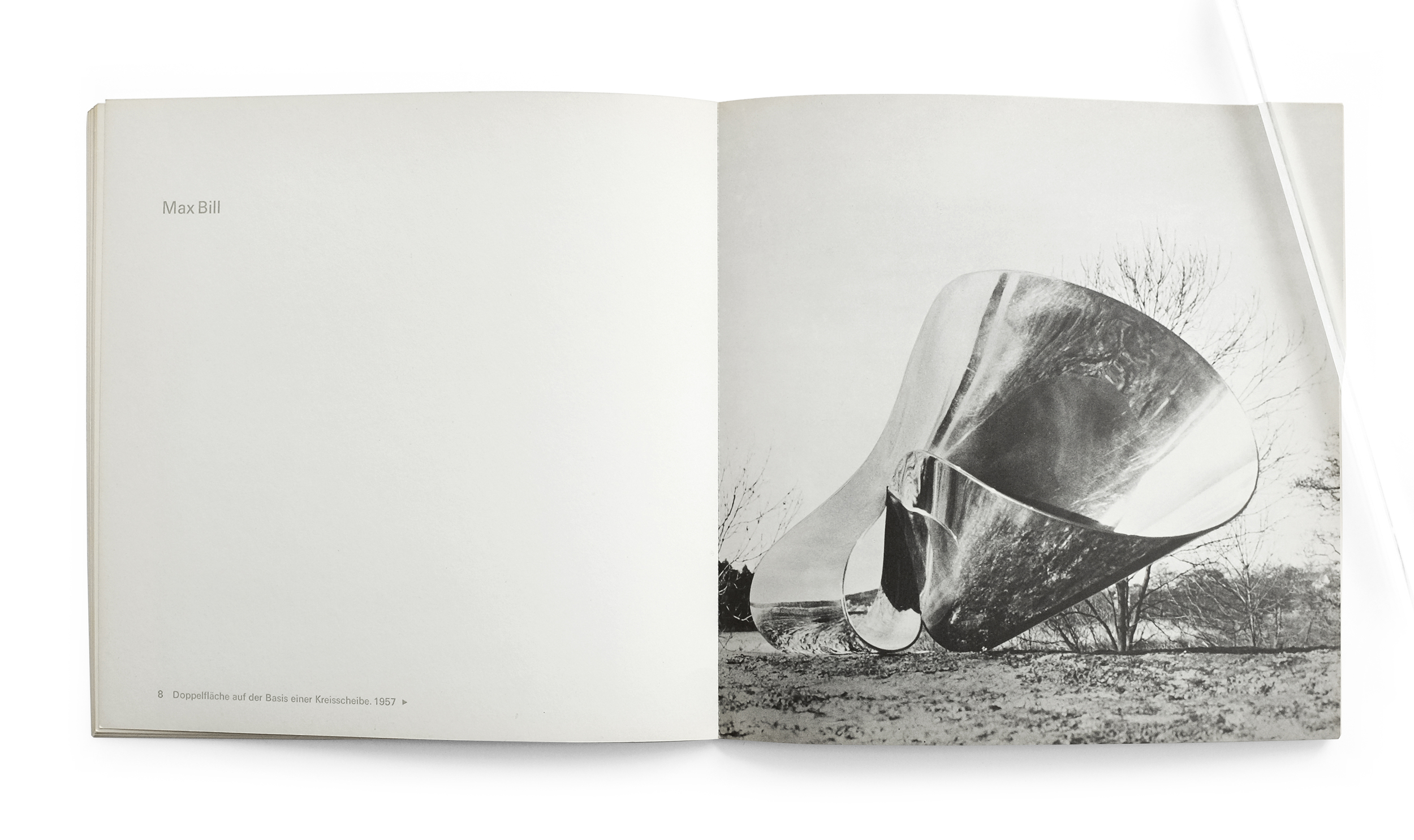

Moon and Space is a perfect example of that sense of reward the reader receives not only for continuing through the book, but for returning back to it again and again. Published in 1969 by Galerie Beyeler (which has ceased to exist and was replaced with the remarkable institution, the Foundation Beyeler), Moon and Space is among a family of exhibition catalogs from that era which are all magnificently designed. I’ve shared one such catalog before—Europa/America—and I hope at some point to post more in the future. But the Moon and Space was my first introduction to this publisher and therefor holds a special place in my heart. The designer is unattributed, however, I believe it is the work of op artist Victor Vasarely who was trained as a book designer and represented by Galerie Beyeler. It bears many signature marks of Vasarely’s designs from the large and playful typsetting of Univers, to the dancing text blocks and images across the page, and finally the liberal interchange of substrates throughout.

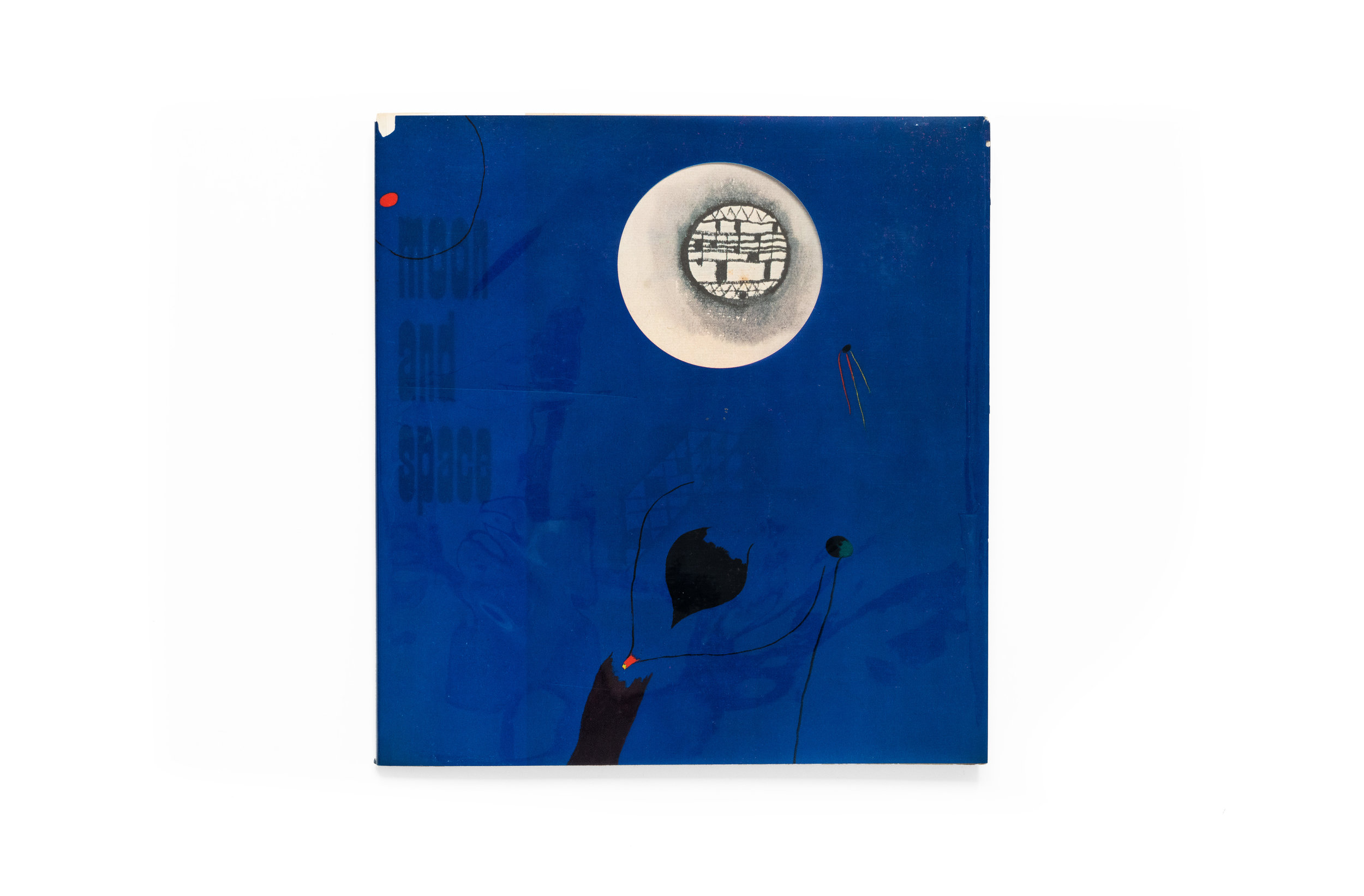

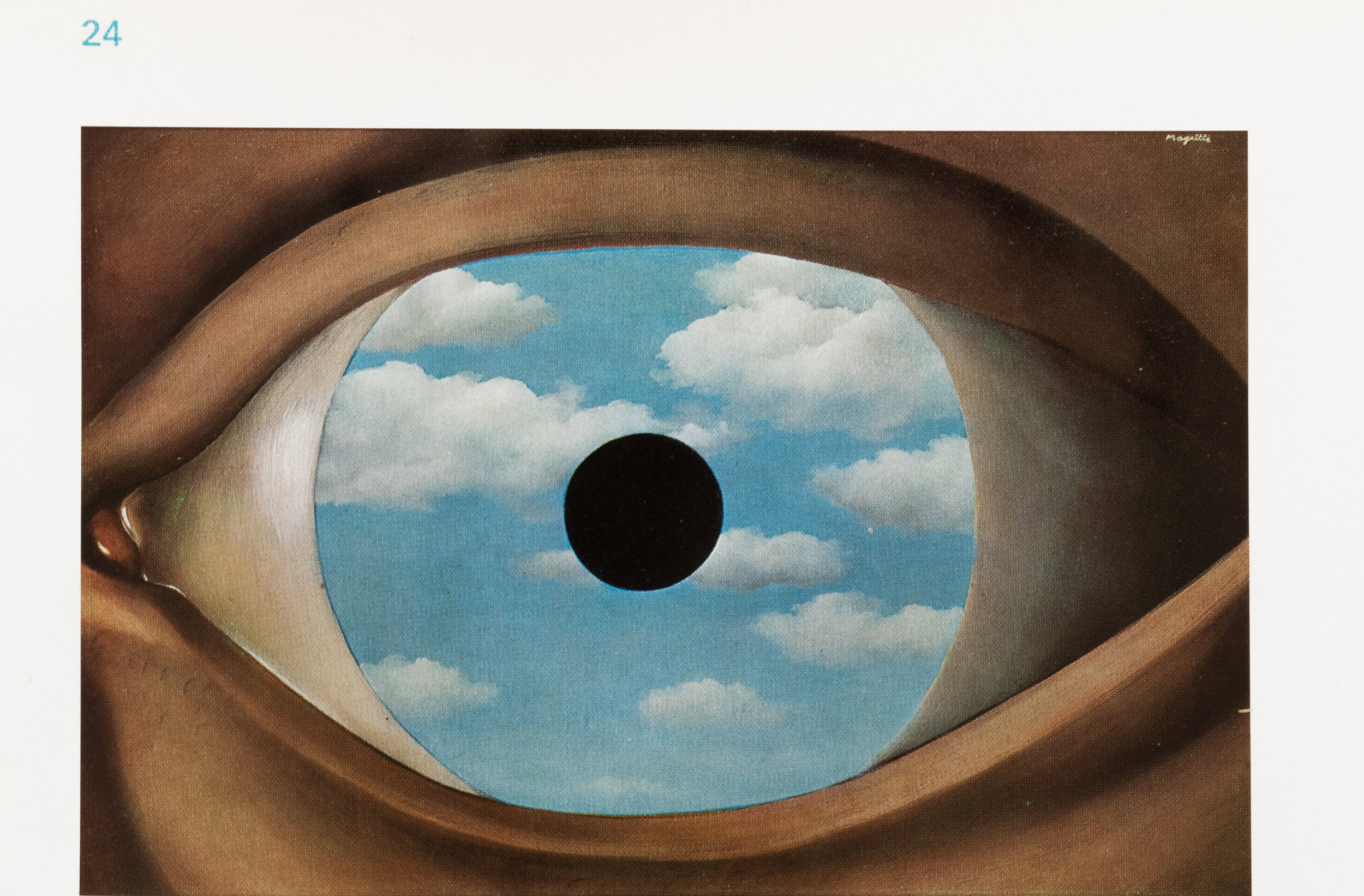

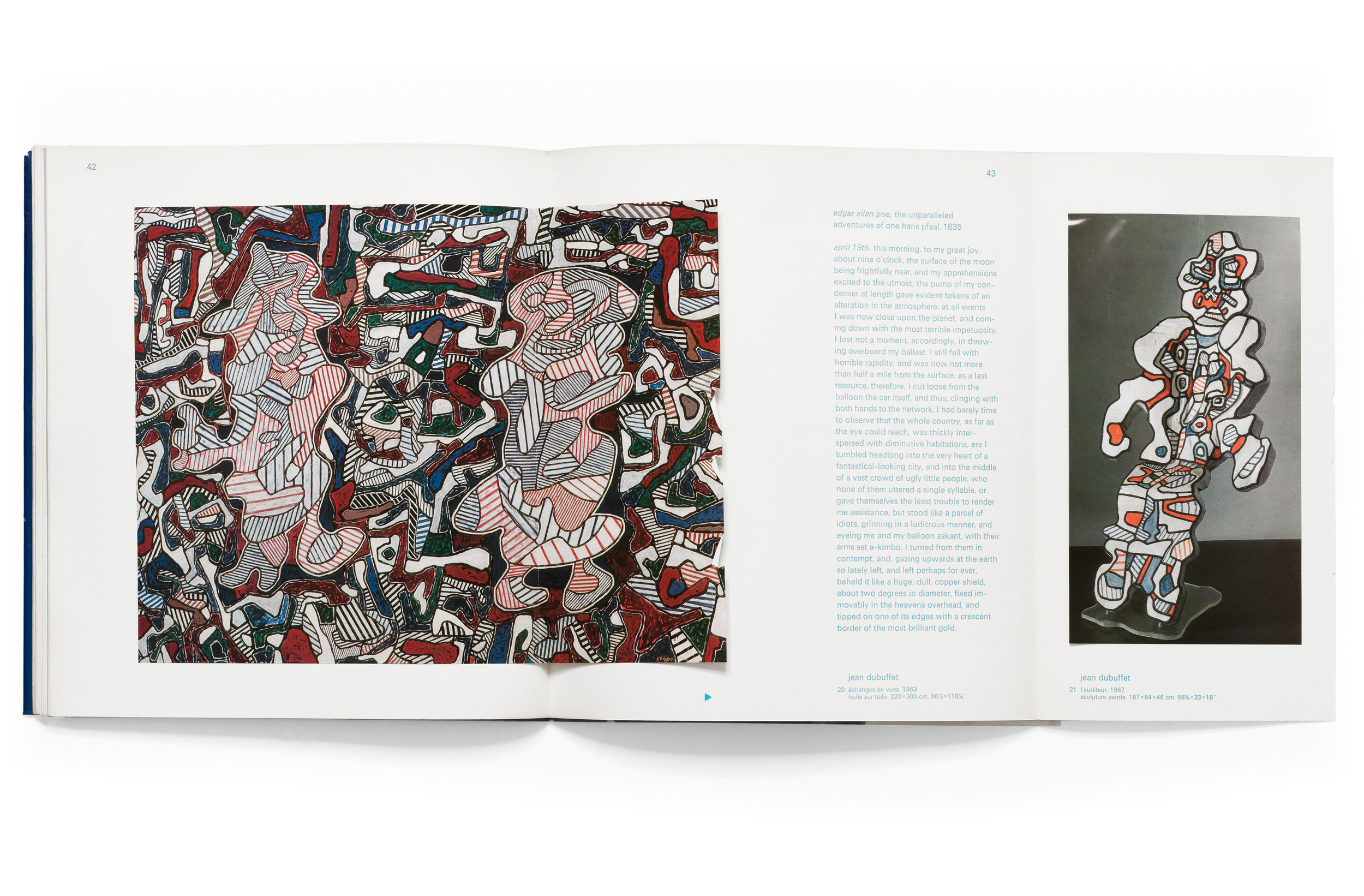

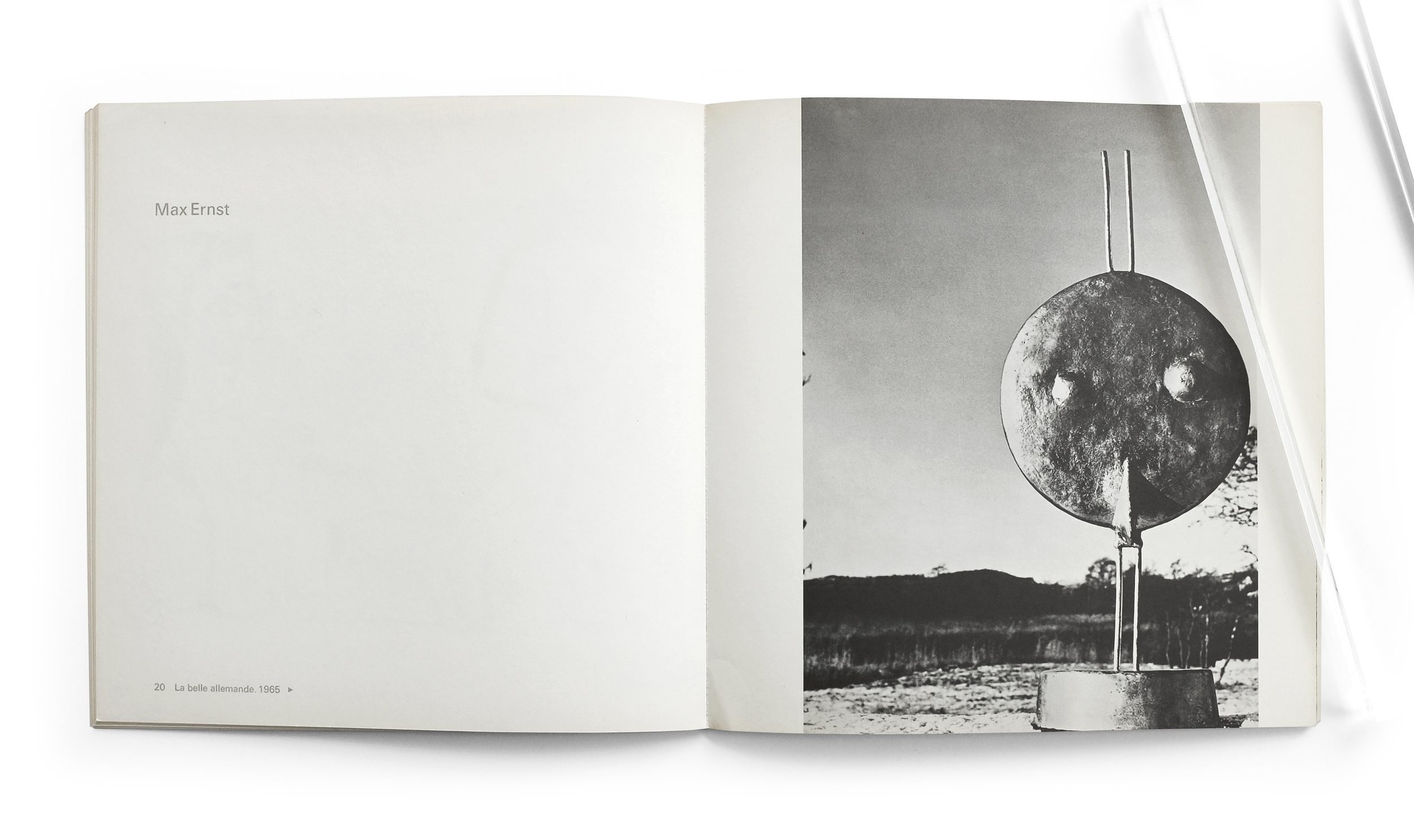

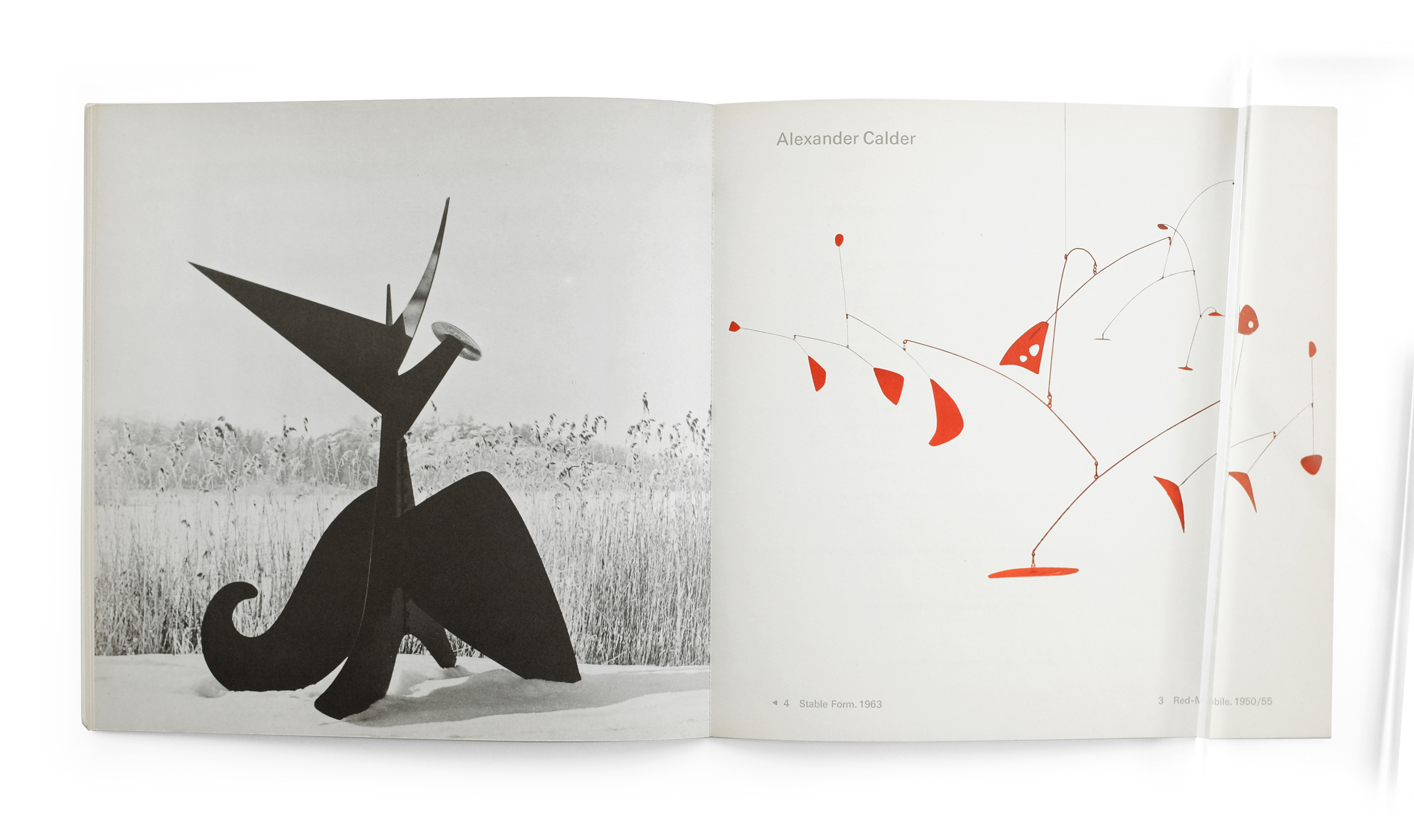

The exhibition itself, as one might surmise, was predicated on artists’ interrogation of the celestial and surreal. Such a theme is music to any designer’s ears and Vasarely surely did justice to such a poetic and open-ended concept. The cover, bizarrely, is actually an acetate wrap which has Joan Miró’s “dream painting” simply titled “Painting” (1927) printed on top. The rich blue hue is further complemented by the transparency and dimensionality of the acetate as its distance from the paper cover underneath varies and alters its intensity. Below the jacket and printed on the cover is a second painting, this time by Paul Klee, along with the title of the catalog in reverse contrast type. What I find so striking about this cover is the intentional distortion of the Miró and Klee.

We’re conditioned to expect artwork to be presented objectively and in a pristine state. Yet here, not only is Miro’s painting die-cut to show Klee’s moon through his dark blue sky, but the wrapper’s translucency gives way to an entirely alternative reading… a kind of third, new painting emerges from the blending of the two. I find it hard to believe that any popular publisher today would sanction such a manipulation of an artwork, and yet in this instance it succeeds in creating a disorienting and surreal bridge to the dream-like content within.

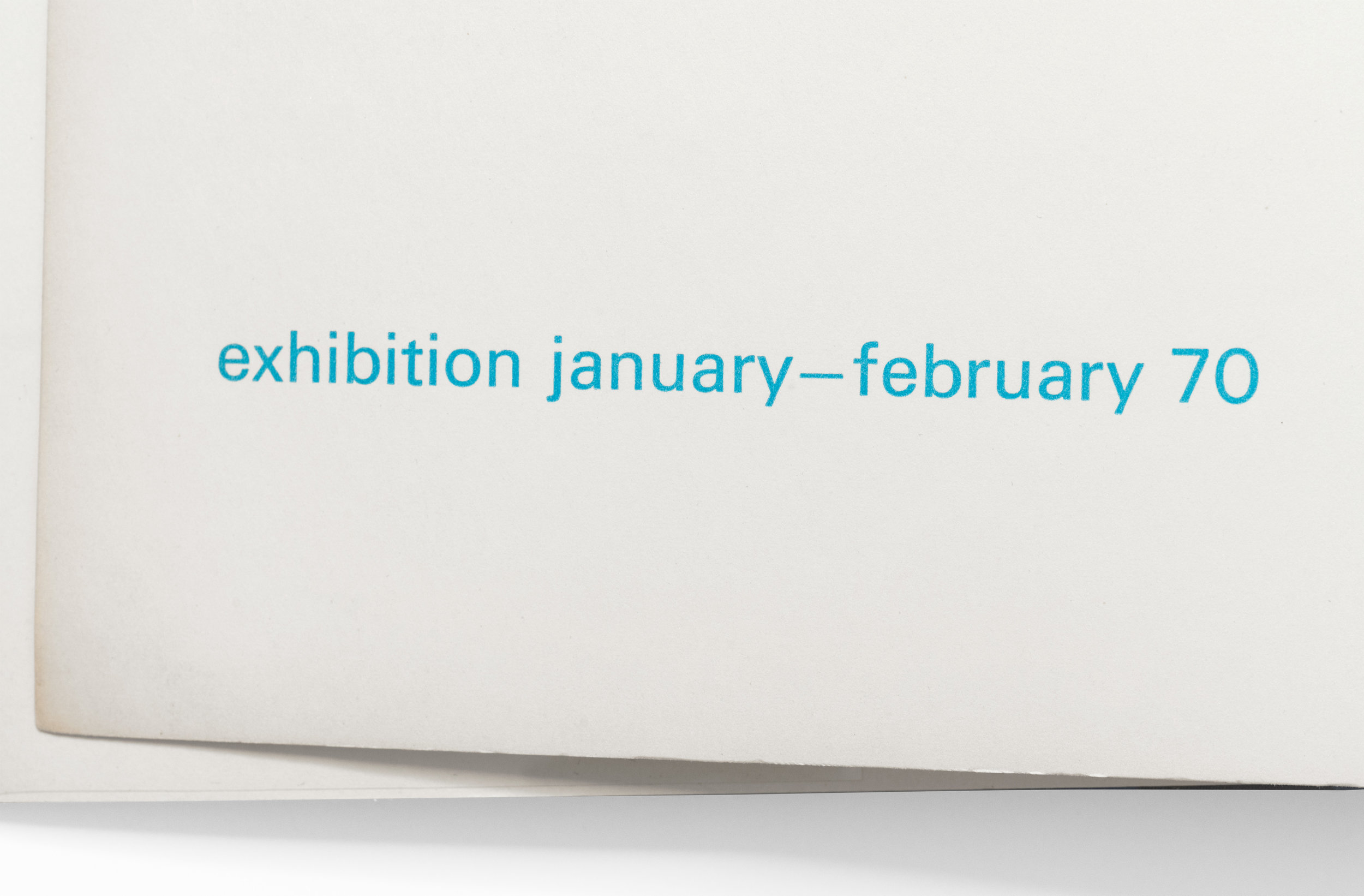

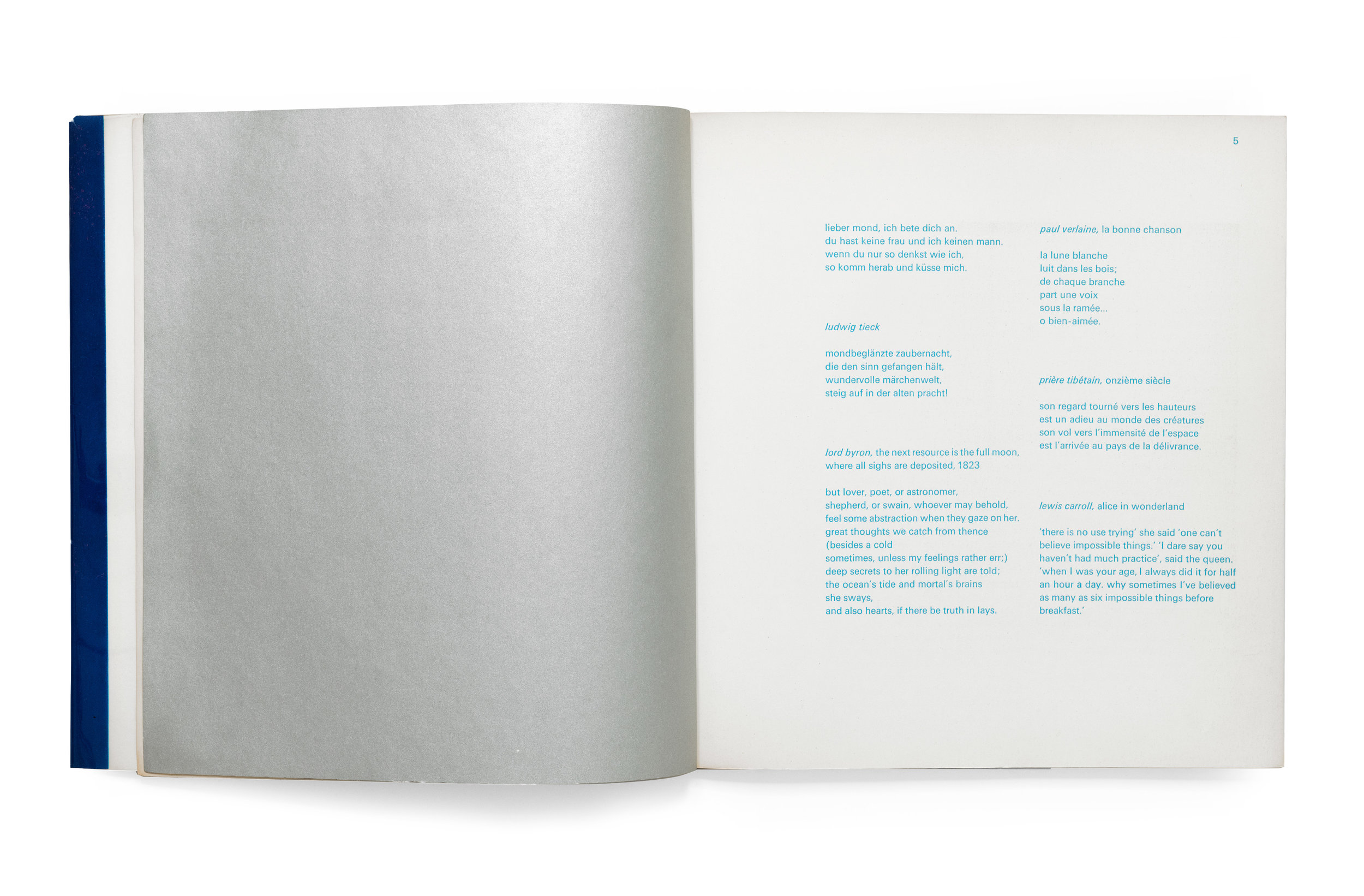

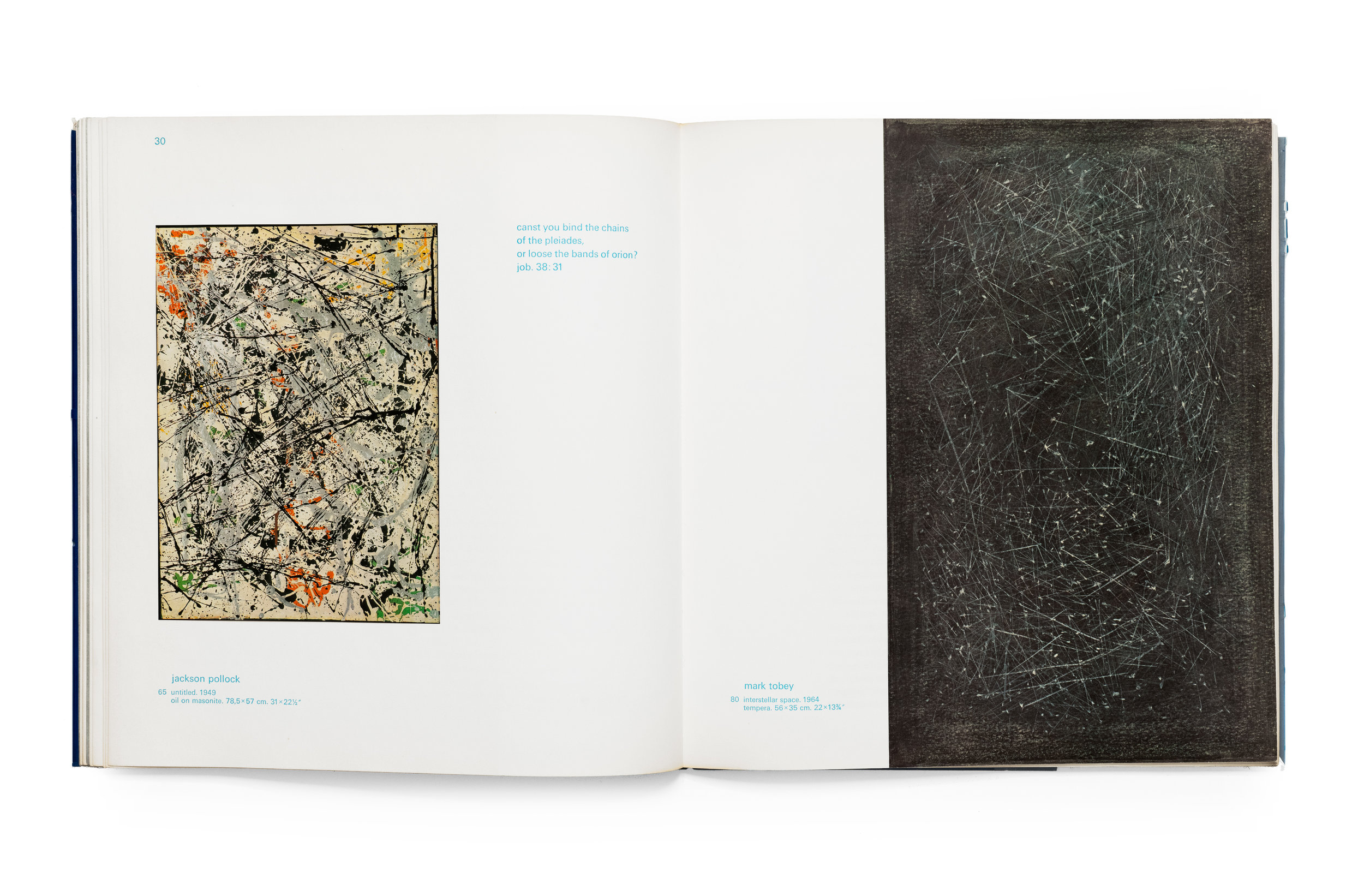

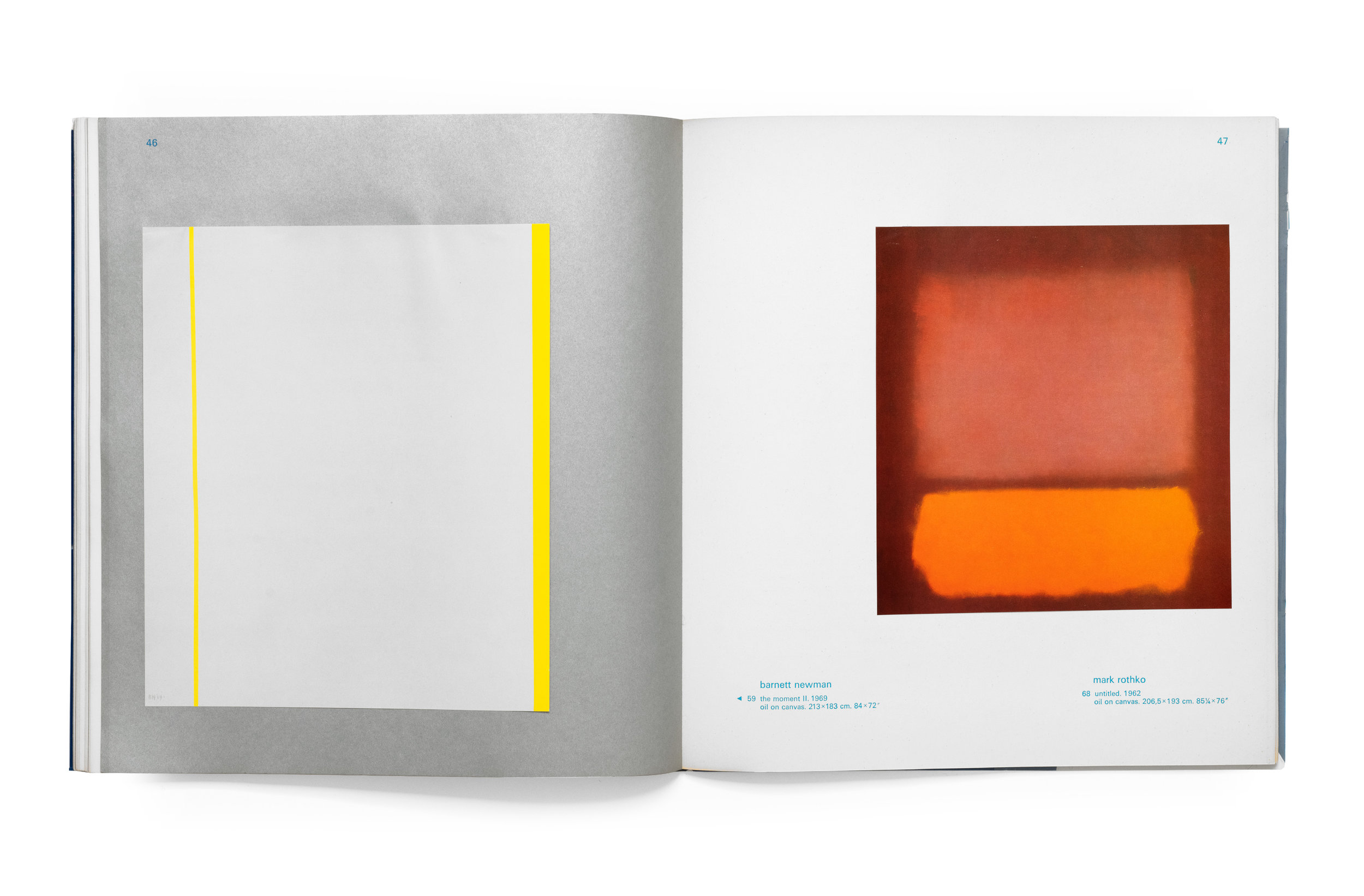

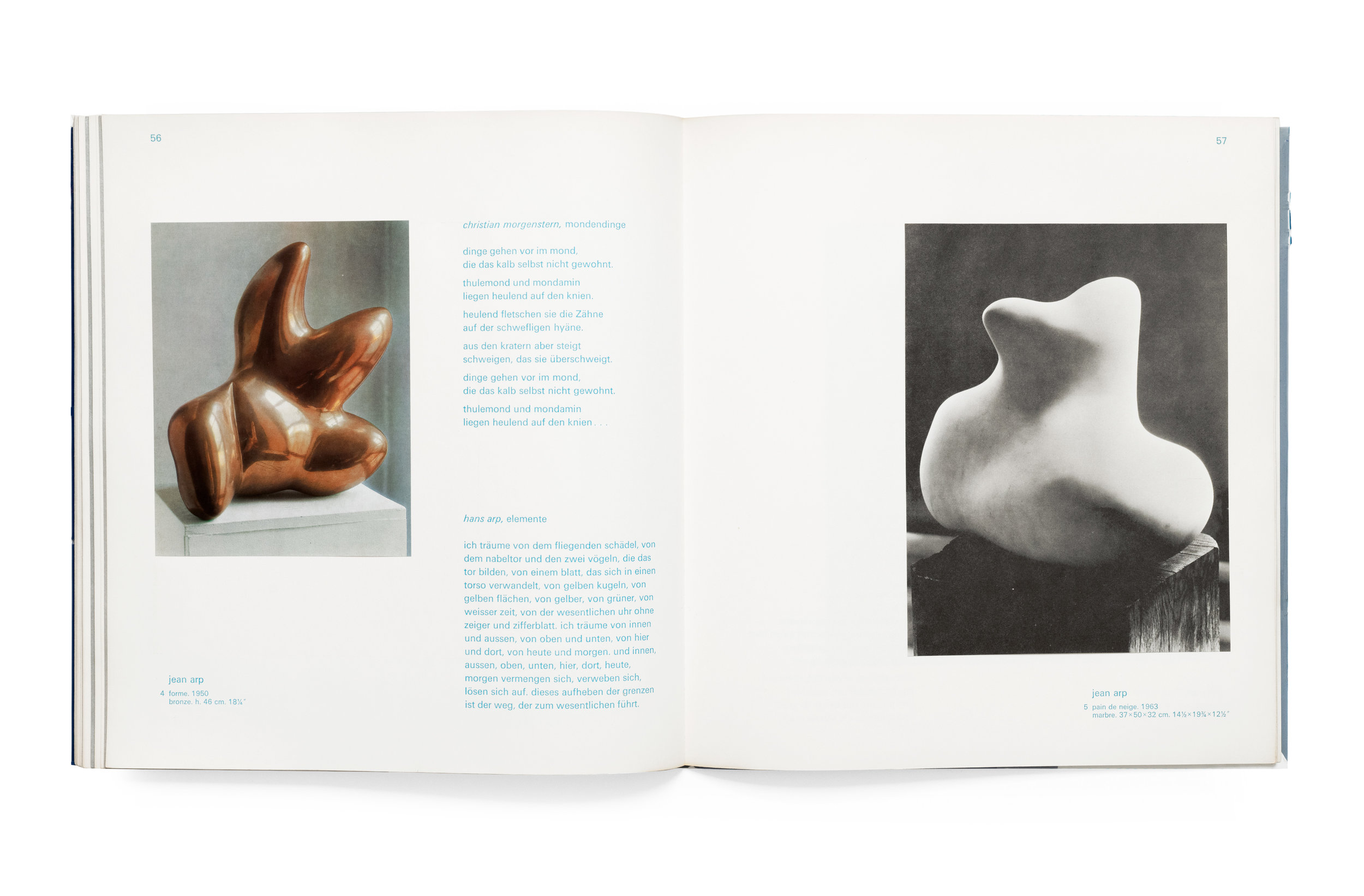

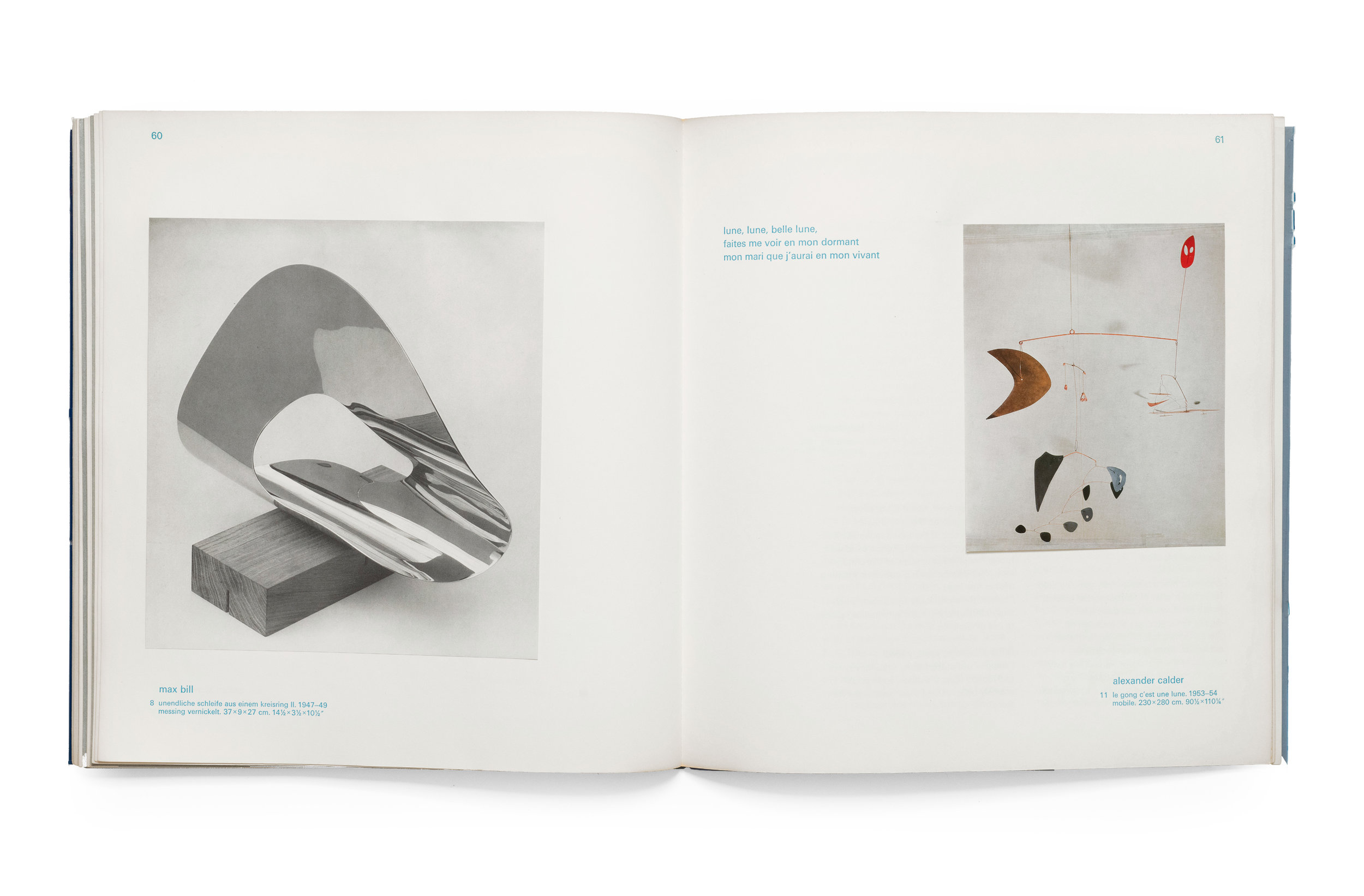

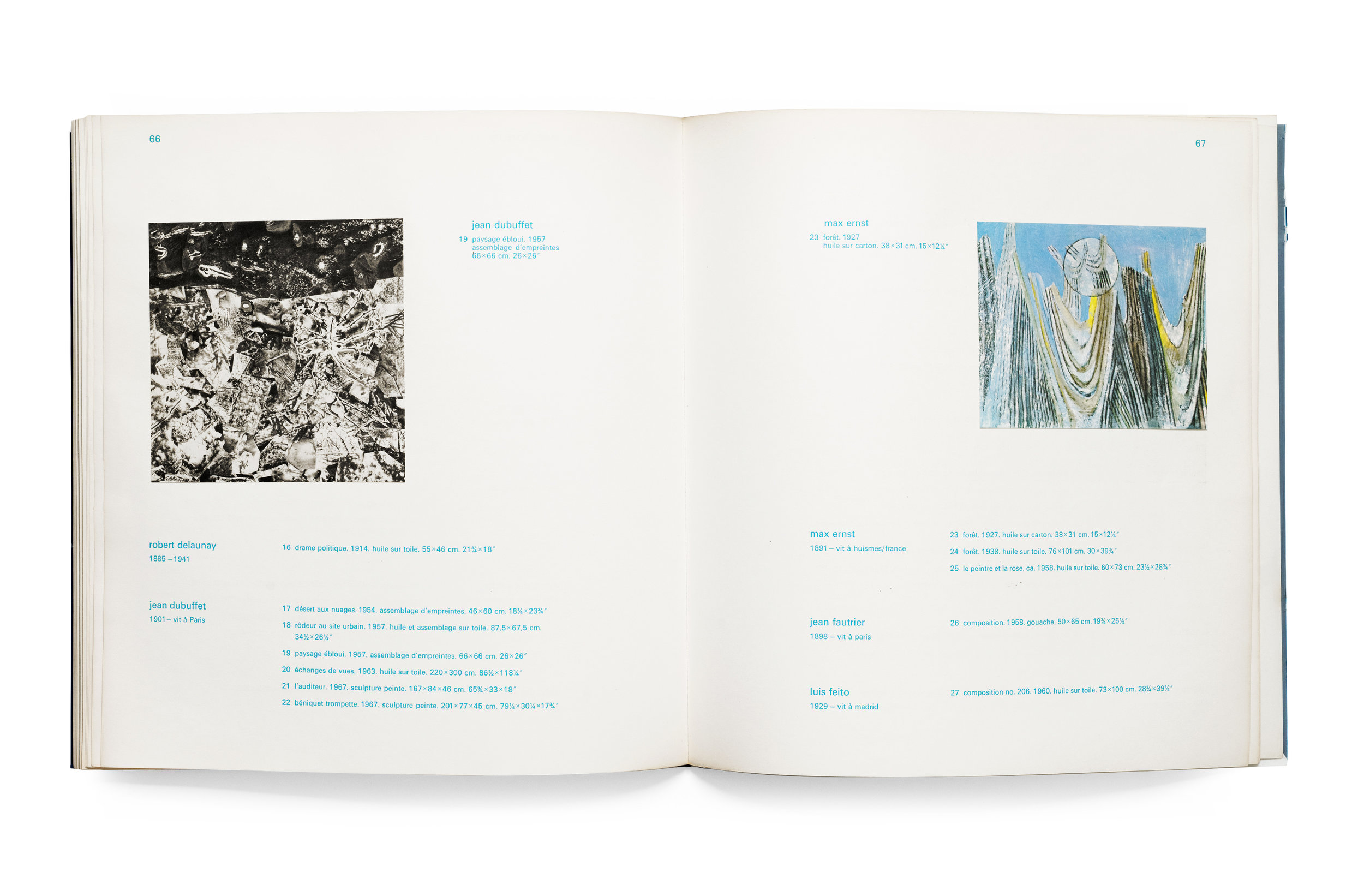

On the title page we’re greeted with a luminescent metallic silver which shimmers against the blue title set in perspective, as well as publisher and exhibition date information. It’s also worth noting that the decision to forgo capitalization throughout the book gives a lovely childlike impression to the experience. On the first page, as well as subsequent pages sporadically throughout the book, we’re presented with excerpts from literature or popular culture which have to do in one way or another with space, the fantastical, or our romance with the unknown. Editor Dr. Reinhold Hohl is responsible for the collection and I commend him for the absence of art-historical references in the text. It completely recontextualizes the experience of the artwork into a broader dimension of human existence. Texts are presented in their original language and range from a writing by Schopenhauer to an excerpt from Alice in Wonderland to NASA transcripts from the Apollo moon missions. The result is, again, a dream-like fugue through text and image, all orbiting this amorphous topic of what lies beyond our perception.

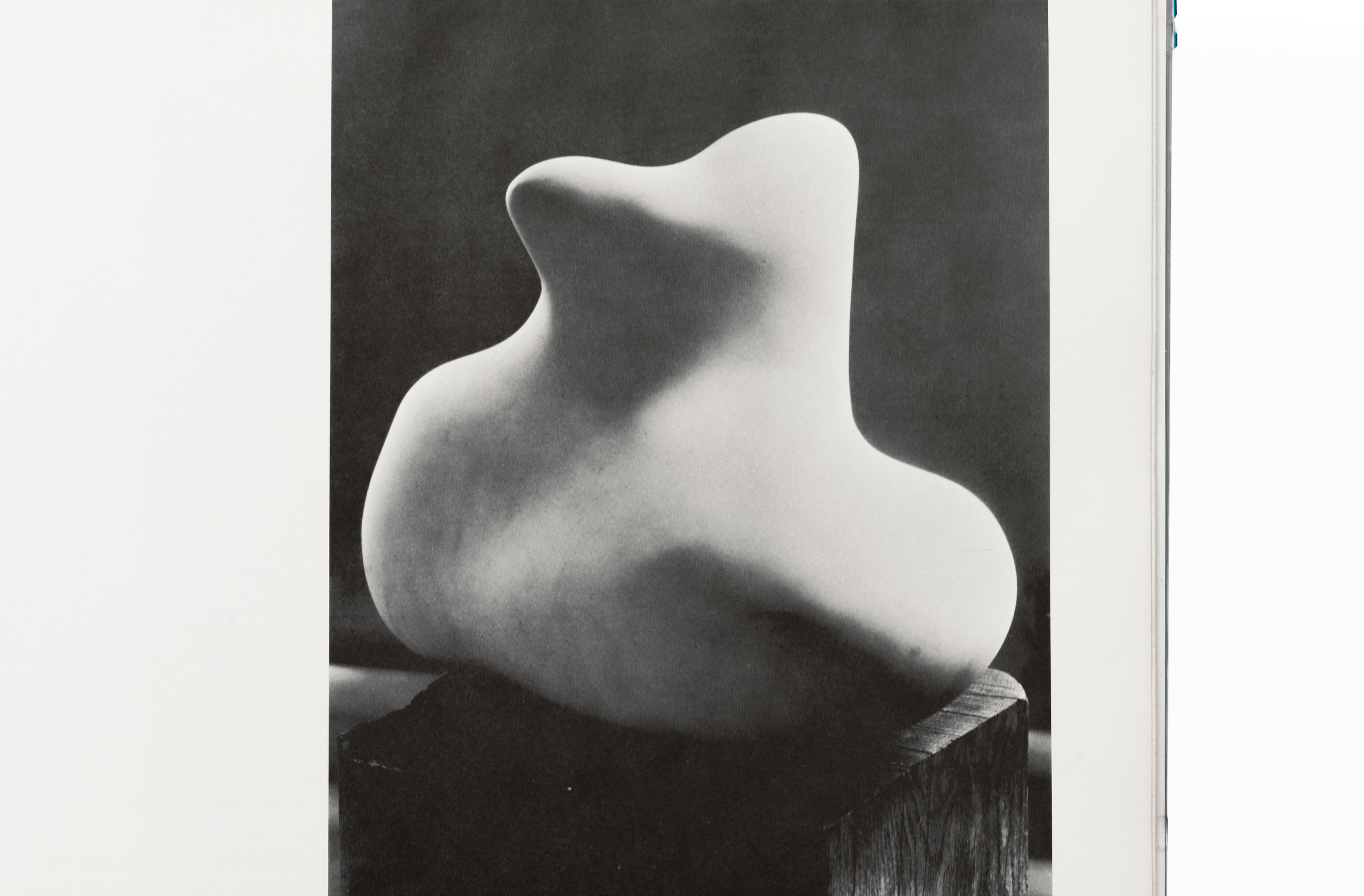

Much like how the text itself shifts author, perspective, and time, the imagery also contracts and expands as it irreverently dances across the pages. The tipped-in color plates add to the liveliness of the spreads as each image flutters about when the pages are turned. And a few gatefold pages add to the mystery and playfulness of this ever-evolving object. Two colors: the rich spot cyan of the type along with the metallic silver pages interweave throughout to create a wonderful play with one another and the artwork.

I don’t mean this to sound pejorative when I say there is an unmistakable silliness to the book’s design. It defies a kind of logical cohesion which one might attribute to Swiss work of the time. The consequence of which is an experience that feels whimsical and childish in a way that is so completely befitting of the subject matter. Flipping through this book, reading the texts, and looking at the abstract works, I’m left with a contented sensation similar to that which you get when you stare into the sky at night and feel the unmistakable tinge of appreciation to know just how little we understand about ourselves and our world.